Commentary – 2022 1st Quarter

1/21/2022

“No man ever steps in the same river twice.”

- Heraclitus

The Great Inflation

“For it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man,” as goes the rest of the quote from the ancient Greek philosopher. While many of the conditions which created the post-Covid stock market boom remain intact, it would be foolish to believe that this is the same river. The tides of sustained inflation and rising interest rates are turning.

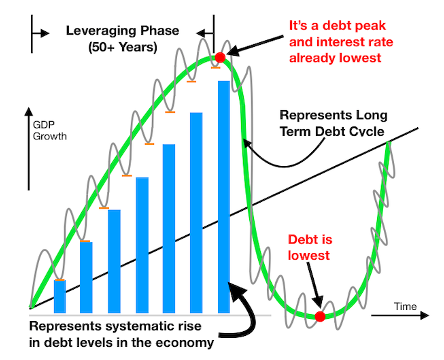

This change is several decades in the making and is best described by the Long-Term Debt Cycle. Ray Dalio, founder of the world’s largest hedge fund, famously stated in April 2020 that he believed Covid-19 would send the U.S. economy into a recession, citing the Long-Term Debt Cycle[1]. This is a macroeconomic trend which defines periods of growth and recession based on economic debt, typically over periods of 50-75 years (see Figure 1, right).

Basically, this is a feedback loop. Borrowing money increases income and spending over time. This, in turn, increases net worth and borrowing capacity, which then increases income and spending. And so on, and so on until, eventually, the debt bubble bursts. Essentially, the amount of debt, as well as interest rates, are indicators of how close the economy is to deleveraging.

There have been two substantial events in this timeline over the past century—the establishment of the Bretton-Woods system after World War II, as well as its effective termination with the abolishment of the gold standard in 1971. The latter was, effectively, the start of the current cycle.

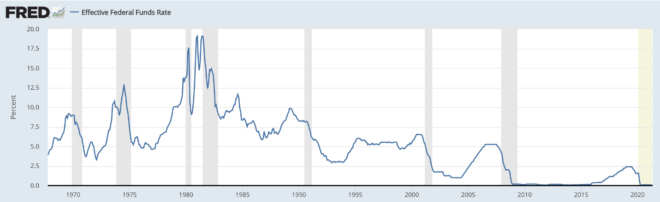

The following 50 years, up until today, have been a period of aggressive leveraging and GDP growth. Federal debt, corporate debt, and household consumer debt are all at record highs[2]. Interest rates move in the exact opposite direction, as seen in Figure 2 (below).

After the economic crash of 2008, interest rates hit near-zero. In a Long-Term Debt Cycle, this is referred to as the “Debt Peak,” indicating that deleveraging is around the corner. Indicative of the name, additional debt is not possible at the debt peak. Therefore, to stimulate economic recovery after the Great Recession, the Fed gradually increased the money supply.

In 2016, the Fed began to increase interest rates to contract the money supply and prevent inflationary effects. The economy was 4 years into the process of deleveraging when Covid-19 pushed the Fed back into economic stimulus mode. As the debt peak meant there was no money for the government to borrow, the economic stimulus was funded by printing new money.

This means that the U.S. economy has been at a debt peak since 2008, with a brief step towards deleveraging, followed by a face-first dive back into the debt peak. 13 years of a debt peak seems counterintuitive, but consider this—for most of economic history, currency had intrinsic value (i.e., gold coins). So, when money ran out, economies were forced to contract. The abolishment of the gold standard meant that when a currency reaches its debt peak, central banks can keep the ball rolling by simply adding more. This, in Modern Monetary Theory, is known as the “Theory of Unlimited Money.”

Unfortunately, when the economy is at a debt peak, the increase in money supply puts more stress on the system. Two potential ways to restore order would be a restructuring of debt or a massive acceleration of GDP. These would come from either a large-scale default, a la 2008, or a war-time level of mobilization, both of which seem unlikely. The economy is slowing, not stalling, and appears healthy.

The third way that an influx of new money can help to “pay” for the debt is by devaluing the currency. In short, absent a market correction or rapid growth, inflation is the result of this type of monetary intervention. This will, in turn, prompt the Federal Reserve to increase interest rates to combat the threat of runaway inflation and deleverage the economy off its debt peak. As of now, it has been stated that the central bank plans to hike rates 3-4 times this year and 3-4 times next year.

Although the year-over-year increase in the Consumer Price Index was close to 7% in 2021, we are not suggesting that there will be runaway inflation. Buried in this number were pockets of transitory inflation caused by supply chain issues, purchasing manias, and demand pockets.

Many reasons were offered in mid-year to show that higher inflation numbers were merely a facet of temporary effects from the pandemic. But there is a stickiness to general consumer price inflation that the U.S. economy has not seen in decades. The Bureau of Labor Statistics started to publish an index that excluded food, fuel, shelter, and used cars and trucks to omit most of the weirdest effects of the pandemic. Even with those items excluded, inflation continues to rise and is now at a 30-year high[3].

Most analysts, the Federal Reserve included, presume that inflation will continue around 3% over the next decade[4]. This is significant for two reasons. First, the Fed’s target rate is 2%. They are admitting that, in an ideal scenario, inflation will persistently be 50% higher than their target. Second, investors and corporations have been accustomed to both near-zero inflation and interest rates for the better part of the last decade. Adjusting to this new market regime may be tumultuous.

Investment Outlook – 2022

2021 was a remarkably placid year. The range of returns in the stock market was a third of the average over the past 40 years. The conclusion from this is simple—there is a high probability that 2022 will be more volatile. We have already started to see this in the first few weeks of the year. Traders are adjusting their expectations for monetary policy, and as they brace for higher rates, are undershooting and overshooting along the way. Both stocks and bonds are showing sharp moves towards belief of an overheating economy. As value has been lagging for a decade, and real yields (adjusted for inflation) remain steeply negative, there is much further they could go.

This year will be defined by a hawkish Federal Reserve, less fiscal stimulus, and softer corporate earnings. There is likely to be fiscal drag for the first several months as Joe Biden’s Build Back Better bill was forestalled. Furthermore, as detailed earlier, a return of inflation will be at the forefront.

- What It Means for Stocks

Contrary to popular belief, stocks are not necessarily “due for a correction.” However, inflation and increasing interest rates do change the expectations for equity markets.

Value stocks (i.e., lower price/earnings ratios and dividend payers) appear to be poised to take the limelight away from growth stocks. Many analysts have been calling for this rotation for the better part of the last decade, but without sustained inflation growth stocks have reigned as the more favorable investments. As companies adjust to supply chain issues, higher borrowing costs, and potentially slower earnings growth, healthy free cash flow will be an important factor to investors. We will continue to be favoring more conservative, stable equities with an eye towards buying opportunities if the broad market experiences a correction.

As mentioned, it is highly likely there will be more volatility in 2022, which simply means a wider dispersion of outcomes. With the return of inflation, it may be time to re-think the “buy tech and let it ride” mantra of the past decade.

- What It Means for Bonds

Increasing interest rates are a headwind for bond portfolios. This risk is exacerbated by inflation, since purchasing power is eroded at a faster rate than the yield which can be earned. Short-term Treasury bond ladders will continue to be advantageous as they allow investors to take advantage of rising rates in real time. Inflation-adjusted bonds, such as TIPS, will also need to be considered to hedge against the risks of inflation on bond portfolios.

The bottom line is that conservative investors are hurt more in an inflationary environment. Stocks tend to do well, as inflation means economic growth. It will be important to diversify bond portfolios by evaluating alternatives such as dividend stocks, emerging markets bonds, private real estate, high yield credit, and preferred stocks.

Financial Plan Strategy Implications

The return of inflation impacts more than investments. Everyone has an inflation story from this past year. Maybe it was as simple as the grocery store checkout line—the price of bacon was up 18% and oranges were up 10%[5]. Or, perhaps, you tried purchasing a new vehicle, only to be told that delivery would take over a year.

Luckily, a tight labor market means that wages are growing. So much of inflation, at least for those in the workforce, is being offset by pay increases. But in 2022, the bump in take-home pay will potentially have more to do with deductions rather than wage growth, thanks to inflation indexing.

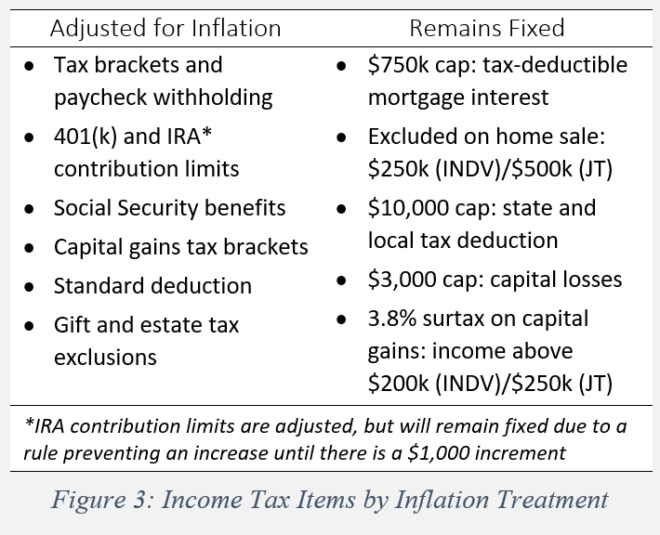

Enacted in 1981, after years of inflation as high as 14.8%, inflation indexing automatically adjusts many, but not all, key tax provisions (see Figure 3, right).

This will reduce income taxes for most Americans after a year of breakaway inflation.

It is important to understand that not all these items are adjusted at the same rate. For example, Social Security benefits are set to be raised by 5.9% in 2022, while income tax brackets will be raised by 3%[6]. This is due to different inflation measures being used, by law, for different items in the tax code.

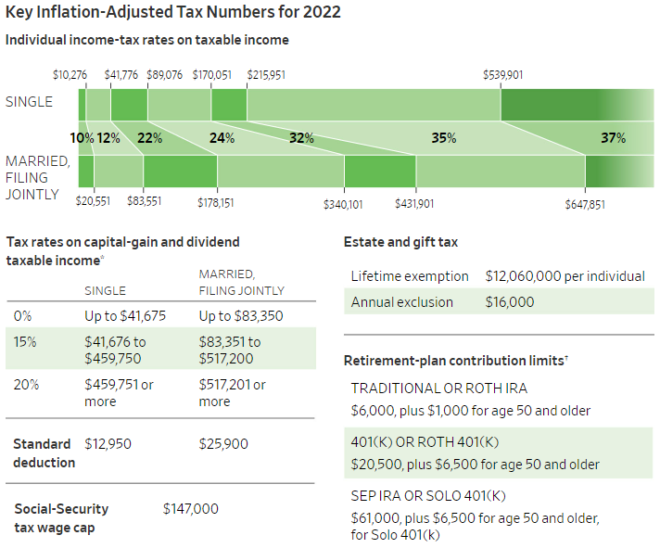

To get a better feel for exact numbers, the Wall Street Journal recently released a graphic showing all the key tax numbers for 2022, after inflation indexing (see Figure 4, below).

As we step into 2022, the economy is in the mid-to-late stages of the business cycle. Growth is likely to slow, but not stall. Rising interest rates and sustained inflation appear to be themes that will be recurring for years to come. We anticipate several interest rate hikes this year and volatility in the stock market. A close eye will need to be kept on fiscal policy initiatives, as well as monetary policy as the Federal Reserve will likely address their ongoing “tapering versus tightening” calculations.

Overall, we remain optimistic yet vigilant.

We hope you found our comments helpful and informative. If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to contact us. We welcome the opportunity to discuss our thoughts in greater detail. Thank you for your continued confidence in Planning Capital.

Sincerely,

The Planning Capital Team

Author

Daniel B. Brady, MBA, CFP® │ Partner

Contributors

Richard W. Bell, Jr., CKA® │ Partner

David A. Emery, MBA, CFP® │ Senior Financial Planner

Jay D. Ahlbeck, CLU®, ChFC® │ Senior Financial Planner

Paul C. McClatchy, MBA, CFP® │ Senior Financial Planner

[1] Tom Huddleston, “Ray Dalio predicts a coronavirus depression,” CNBC, April 9, 2020

[2] St. Louis Federal Reserve, FRED Database, December 31, 2021

[3] John Authers, “Sic Transit 2021,” Bloomberg Points of Return, January 13, 2022

[4] David Kelly, “Pumping the Brakes on the U.S. Economy,” J.P. Morgan Guide to the Markets, January 3, 2022

[5] BlackRock Market Outlook, January 12, 2022

[6] Laura Saunders, “What Inflation Will Do to Your 2022 Taxes,” The Wall Street Journal, January 7, 2022