Commentary – 2022 3rd Quarter

7/20/2022

“The wise man does in the beginning what the fool does in the end.”

- Warren Buffett

Hiking into Bear Territory

Well, it’s official; stocks have entered a bear market with the S&P 500 drawing down 24% in the second quarter. This is the worst start to a year for the S&P 500 since 1932. It also appears likely that the technical definition for a recession, two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth, will also be met. If this is the case, the media’s “recession alarm” will certainly spread more pessimism.

While a return to volatility is jarring, investors often accept that stocks can experience sharp decreases. But the double-digit drop in bonds, and in some corners of the market equity-like drawdowns, has been particularly painful at a time where portfolio ballast is needed. A recent article from The Wall Street Journal put the current bond market into a surprising historical perspective[1] –

“The U.S. bond market has had positive returns, before inflation, in all but four years since 1976. Even in 1994, when the Federal Reserve raised interest rates 2.5%, bonds lost only 3%.

Almost never has the U.S. bond market lost as much money as in 2022, according to Edward McQuarrie, a professor at Santa Clara University who studies asset returns over the centuries.

Long-term Treasury bonds lost more this year than the previous record of the 12 months ending in March 1980. The broad bond market has performed worse so far in 2022, he says, than in any complete year since 1792 except one. That was all the way back in 1842, when a deep depression approached rock-bottom.”

The worst bond market in 160 years. Furthermore, the correlation between equity and fixed income in 2022 has not been seen since the 1990s[2]. While these correlations were much more commonplace in the decades of the 1970s and 1980s, it is quite unsettling today.

The backdrop for this environment continues to be two-fold—inflation and the Federal Reserve.

Though inflation hit a new four-decade high of 9.1% in June (the highest since November 1981), market sentiment on inflation has improved. The Bloomberg Commodity Index has fallen 18% from its 2022 peak, copper by 33%, lumber by 54% and Brent crude oil by 22%[3]. Expected inflation over the next five and 10 years, based on the pricing of inflation-indexed bonds, have both dropped to the 2-2.5% range, near the Fed’s 2% target.

It is certainly better to have bond and commodity markets expecting inflation to go down rather than up, but the Fed has made it clear it wants to see actual inflation go down—sentiment alone won’t cut it.

While inflation will likely decline over the coming year as gasoline prices stabilize and supply chains improve, where it will settle is unclear and potentially concerning. In other words, the underlying trend rate of inflation if the most volatile, temporary price swings are excluded may still be a problem. No single measure captures that trend perfectly, but a decent approximation comes from the Dallas Fed’s trimmed-mean personal consumption inflation index. It was 4% in May, double the Fed’s target (See: Figure 1).

In response, the Federal Reserve has turned decidedly hawkish. It raised interest rates by 0.75% in June which was the largest hike since 1994. The central bank also signaled that it intends to raise rates several more times this year so it can tamp down inflation. A second hike of 0.75% or 1% has been suggested, which would total a 2-2.5% increase within 5 months.

This is likely to be the most aggressive rate hike schedule in such a short timeframe since the tenure of Paul Volcker in the late 1970s and early 1980s. At the time, inflation topped out at over 14% and the federal funds rate was over 12%. Volcker was notorious for his aggressive approach to inflation, but the contrast of the federal funds rate in the 1980s compared to today is striking.

To compound the problem, the Federal Reserve balance sheet has ballooned to close to $8.5 trillion. Many economists theorize that to get “back to normal” this number needs to be reduced by half. The central bank stopped purchasing bonds in March and started to let maturing bonds roll off (i.e., not reinvesting proceeds of Treasury and mortgage bonds) last month. Currently, this is to the tune of $57.5 billion per month which will increase to $95 billion per month in September[4].

The Fed has a monumental task ahead of itself and is well behind the 8-ball. At this pace, it will take over 5 years for the balance sheet to get back to optimal levels. Furthermore, this monetary tool did not exist in the 1980s. Implementing interest rate policy to combat inflation is now more complex, the outcomes are less predictable, and the historical corollaries are more limited.

It is therefore not surprising that investors have often blamed the Federal Reserve for market routs. This is, however, a double-edged sword—going back to 1950, the S&P 500 has sold off at least 15% on 17 occasions and, on 11 of those 17 occasions, the stock market managed to bottom out only around the time the Fed shifted toward loosening monetary policy again[5].

Getting to that point may be painful.

We’ve talked about the long-term debt cycle in recent quarters and how interest rates have been on a steady march downward over the last 30-40 years. We’ve also mentioned how inflation has been all but absent for much of that time and recessions, such as the tech bubble and the financial crisis, have been marked by excessive speculation. The global economy became ever more interconnected over that timeframe and “easy money” policies were prevalent.

The job for central bankers during this time was quite simple because there was room for both increases and decreases in rates, as well as money supply, to stimulate or slow growth.

In their mid-year global outlook, Blackrock referred to this period as “The Great Moderation.” They are predicting a changing of the guard as markets return to a regime like the 1970s and 1980s. The Federal Reserve will continue to be faced with a brutal trade off—control inflation at the expense of economic growth or allow inflation for the benefit of economic growth.

Paul Volcker thought the choice was easy.

Economic forces are a major reason for the changing market regime, but the signals of a new era are widespread. A total of 417 of the S&P 500 companies mentioned inflation on their earnings calls for the first quarter. Global supply chains are being reconsidered and redesigned. Political discourse across the globe is becoming increasingly nationalist.

It is likely that inflation, volatility, and return dispersions will become much more commonplace than the last 30 years. The hyper globalization movement is hitting a wall.

To that end, the U.S. dollar has been the ultimate benefactor. With its status as the global reserve currency, this does not bode well for global economic prospects. An overheating economy that cannot be cooled is a problem. Slowing economic momentum (i.e., GDP contraction, a stronger dollar) may be good news, as it tends to indicate that tighter monetary policy is working. So long as a lower inflation print follows, markets should breathe a sigh of relief.

It is important to remember that most recessions are not like the last two. On average, they are around a year. The COVID-19 pandemic and the Global Financial Crisis are still at the forefront of investor’s minds. Perhaps this is the contrarian in us, but this is somewhat good news—consumer confidence (measured by a long-running University of Michigan survey) is at a 50-year low, which typically signals that the market has a rebound on the horizon[6]. Consistent with this outlook, Bank of America’s strategists believe that equity investors have reached “full capitulation,” with the cash holdings and equity underweights of stock investors at a 20-year high[7].

Furthermore, the underlying economic fundamentals still look good and the impact of COVID-19 on the economy continues to fade. There is a low unemployment rate, healthy payroll growth, and sustained job growth. The “four horsemen” of painful recessions (residential investment, light vehicle sales, business inventory, and business fixed investment) do not appear overextended. Corporate earnings also appear resilient.

Optimistic signs amidst a recessionary environment are one reason we are considering the case for a double-dip recession. This is classified as a mild recession, followed by a bounce back, then followed by a more severe recession. Robert Heller, a Former Member of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, published an article in Barron’s last week addressing this very concern[8] –

“Real GDP decreased at an annual rate of 1.6% in the first quarter of this year and data published by the Atlanta Fed pegs the growth rate for the second quarter at negative 1.9%. Many economists regard two quarters of negative growth as a recession, but it is up to the National Bureau of Economic Research to make the official call.

However, Federal Reserve policy is still highly stimulative. Longer-dated treasury bonds offer only negative rates of return. If the policy of the Federal Reserve were truly restrictive, one would expect the fed funds rate and Treasury yield curve to be above the inflation rate.

The prevailing financial conditions are more indicative of further positive economic growth prospects than a continuation of the current mild recession. Consequently, we may look forward to a resumption of economic growth in the second half of the year.

That may be good news for the immediate future, but it would do little to rein in the current fires of inflation. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell has expressed several times his determination to bring inflation under control.

If the promised restrictive monetary policy measures are implemented in the second half of this year, the economy will slow down significantly early next year—especially in the interest-rate sensitive sectors.

And that would be the good news. The bad news would be if the Fed caves into the enormous pressures it will face because of the rising cost of servicing our ballooning national debt and does not raise interest rates sufficiently to beat down inflation now. That would weigh down the economy for the indefinite future with all the inefficiencies of high inflation. Fortunately, Powell has made clear that this is not an option.”

This would again be a callback to the 1980s—the stock market had an initial dip occurring the first three quarters of 1980, followed by a second dip that lasted from the third quarter of 1981 until the fourth quarter of 1982. It is certainly possible that the first half of 2022 will be considered a mild recession, to be followed by a more severe recession in the future.

So long as underlying inflation is high, the Federal Reserve is not your friend.

Don’t Forget Your Compass

To recap; high inflation and Fed tightening have, in turn, led to fast rising mortgage rates and this, in combination with fiscal drag, an over-valued dollar, record-low consumer sentiment and stock market losses, is rapidly undermining economic momentum.

For investors, these concerns need to be assessed relative to both much more attractive valuations than at the start of the year and a rational view of the risk of recession and the economic and policy landscape it could leave in its wake.

For investment strategy, this means a few things:

- A greater focus on company fundamentals (competitive position, income statement, balance sheet) for stocks

- Reigning in of speculative asset classes and capital-intensive industries

- Using dollar-cost averaging when putting new cash to work in the portfolio

- There will be more risk in bonds, but also more opportunity

- International will likely continue to struggle

What we like right now:

- Cash

- I-Bonds through TreasuryDirect

- CDs/Treasuries with short-term maturities, either directly through a banking institution or in a brokerage account as part of the portfolio’s bond exposure.

- Equities

- Dividend “Aristocrat” companies who have demonstrated the ability to not cut their dividend payments to shareholders during the last 20 years (three recessions)

- Quality Growth focused on fundamental analysis and lower multiples rather than the speculative, debt-heavy companies which have enjoyed the limelight for 20-30 years

- Perhaps the most important piece of guidance: don’t sell low

- Fixed Income

- Municipals are currently showing tax-equivalent yields not seen in decades

- Inflation-Linked Bonds continue to be our preference for core bond exposure

- Risk Management Alternatives – Infrastructure and Private Real Estate both offer attractive yields with non-correlated returns and lower volatility than their equity counterparts

It is important in this type of market to also think carefully about investment time horizon. At Planning Capital, we are naturally wired to be long-term investors. That means we tend to think strategically (3-5 years) and not tactically (6-12 months).

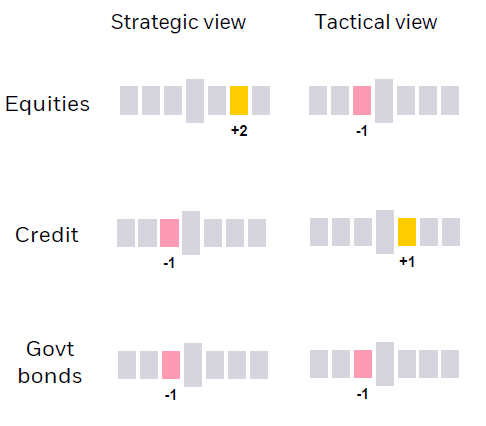

Figure 2 shows the BlackRock Investment Institute’s views on the major asset class from both a short and long-term perspective[9]. Positive indicates overweight (bullish) and negative indicates underweight (bearish). The divergence also becomes more granular when comparing domestic to international.

Our takeaway is that portfolio construction and rebalancing will require a mix of both patience and conviction in this new era of investing. Balancing these will test the mettle of investors.

Volatility has returned.

We hope you enjoyed our comments. If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to contact us. We welcome the opportunity to discuss our thoughts in greater detail. Thank you for your continued confidence in Planning Capital.

Sincerely,

The Planning Capital Team

Author

Daniel B. Brady, MBA, CFP® │ Partner

Contributors

Richard W. Bell, Jr., CKA® │ Partner

David A. Emery, MBA, CDFA®, CFP® │ Senior Financial Planner

Jay D. Ahlbeck, CLU®, ChFC® │ Senior Financial Planner

Paul C. McClatchy, MBA, CFP® │ Senior Financial Planner

[1] Jason Zweig, “It’s the Worst Bond Market Since 1842,” The Wall Street Journal, 6 May 2022

[2] Lauren Solberg, “Why Your 60/40 Balanced Portfolio Isn’t Working in 2022,” Morningstar, 14 July 2022

[3] Greg Ip, “Beware Wishful Thinking About Inflation and Recession,” The Wall Street Journal, 13 July 2022

[4] Josh Hirt, “The Fed’s plan to shrink its balance sheet, quickly,” Vanguard Expert Insight, 10 May 2022

[5] Akane Otani, “Stocks Historically Don’t Bottom Out Until the Fed Eases,” The Wall Street Journal, 20 June 2022

[6] David Kelly, “Q3 Guide to the Markets,” JP Morgan Asset Management, 30 June 2022

[7] Jacob Sonenshine, “Stock Investors Have Thrown in the Towel, BofA Says,” Barron’s, 19 July 2022

[8] Robert Heller, “This Recession May Be Mild. The Second One Will Be Worse.” Barron’s, 12 July 2022

[9] BlackRock Investment Institute, “Global Outlook – Midyear 2022” July 2022